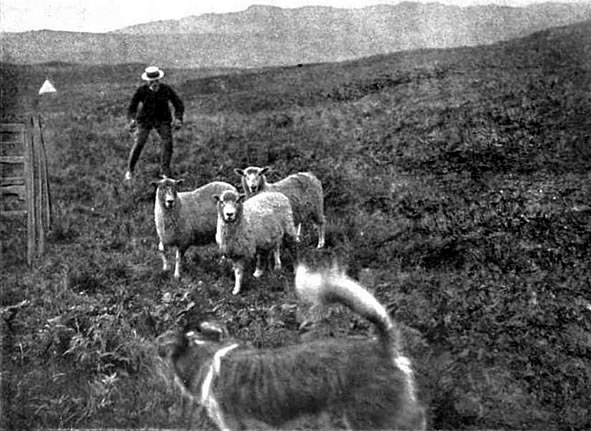

In this story we read and see photos of a sheep-dog trial held in Northern England in 1901. These dogs are the spitting image of English Shepherds as they exist in America today, notice too the upright working style. I should also point out that this trial takes place close to the Scottish border and in the very year that Old Hemp died, therefore any of these dogs could also be progenitors of what would become the Border Collie breed.

The Sheep-Dog Trials at Troutbeck

A Remarkable Test of Dog Intelligence.

By A. Radclyffe Dugmore

Up in the North of England, in the famous Lake Country, there is a small village known as Troutbeck. Here every year the community of sheep-herders gather together to witness a sport as dear to them almost as their very homes, being connected as it is with their actual livelihood. It is a sport absolutely unknown to the greater mass of the people, even in England, yet it calls forth the unqualified admiration of all who see it. For it is a display, not of brute force, nor of human powers, but of the intelligence of dogs. Not ” instinct,” mind you, but quick, thoughtful intelligence.

It is of the North Country sheep-dog trials that I am speaking. While horseracing calls for highly-developed wind and muscle; and hound trials are but examples of speed, endurance, and the natural instincts of the dogs; and human sports, such as jumping, wrestling, running, and the like, need little more than strength and cunning; the dog trials require, beyond all of these attributes, a very high degree of intelligent reasoning power.

For a long time the Troutbeck dog trials have taken place each year in August, and until quite recently the prize given was always a silver cup, which was treasured as a proof of the winning dog’s skill and the herder’s patient training. Now, however, by the desire of the younger participators, money has been substituted.

Friday, August 23, 1901, was the day set for the most recent Troutbeck trials. It was a perfect day, somewhat hotter than one would have expected, with a clear blue sky overhead, intense in color, and almost cloudless.

The course selected was on the Applethwaite Fells, where the rough hillsides are covered with bracken and heather, with gray lichen-coated rocks jutting out here and there in strong relief against the golden browns and yellow of the bracken and the purple of the heather. The fells were treeless from top to bottom; strange-looking loose stone walls encircled the hills, winding their seemingly purposeless way, serpent-like, through crag and hollow; a small stream, almost hidden from view by the tall bracken, came trickling down the hillside. Quite inconspicuous was this stream, and yet it influenced the fortunes of more than one good dog, for the day was hot and the water cool, and many dogs gave way to the temptation and stopped to slake their thirst.

The course along which the dogs were to take the sheep began at the small triangular pen, running thence in a northeasterly direction uphill and to the east of a flag. From there it went northward down hill, across the stream already mentioned, uphill, and between two flags which were placed to the eastward of a high, rocky crag; then nearly due west, crossing a small gully, and passing between other two flags; next southward, along fairly level ground thickly covered with bracken, to and between the last pair of flags; and from there to the finishing pen. The whole distance from start to finish was about three-quarters of a mile.

The man whose dog was working stood on a knoll about one hundred and fifty yards from the starting point, and not until the sheep were almost at the finishing pen was he allowed to leave his place. From the knoll he had to guide his dog as best he could by signs and signals, shrill whistling, and sometimes calling.

Forty-two dogs were entered on the lists, divided into three classes: competitors for Local Stakes for the district within a radius of ten miles from Windermere Railway Station; Special Stakes for the district within twenty miles of the station; and Open Stakes for all comers. Among the principal rules governing the trials were the following: “Any dog that injures a sheep will be disqualified.” “No dogs except those competing will be allowed on the grounds.” “All sheep-dogs entered must have been not less than three months the bona fide property of the exhibitor, and except when competing, must be held by a cord or chain, under penalty of disqualification.” “No person will be allowed with the dog competing except the man working it, and he will be placed where the judged direct.

The number of sheep for each dog was three, two of which were Herdwicks and the third a half-breed. For each trial three fresh sheep are used, these being taken from the herd penned behind the stone wall which marked the southern boundary of the grounds, and placed in the small starting pen.

At 9.30 A.M. the trials commenced, and the first herder, J. R., stood on the knoll, holding in leash his splendid gray dog Laddie. The dog seemed to realize that some special effort was called for to-day, and looked inquiringly first at his master and then toward the judges’ tent. He seemed to be waiting eagerly to be released. The waving of a red flag was the signal for the simultaneous release of the three penned sheep and the anxious gray dog. At once the latter made toward the three bewildered sheep, directed at first by his master’s call, for the bracken was high and hid the animals from the dog’s view.

It was not long before he saw them, however. Without seemingly paying the slightest attention to his master’s call, he hurried them along at a lively speed. Up the stone-covered hillside they scampered till they reached the first flag; then Laddie stopped an instant for orders—a simple whistle, which he understood—and once more the three sheep were off, with the dog following close behind, guiding them carefully and keeping all three closely bunched together as they passed the first of the series of flags. Then, following the master’s signals, Laddie urged them on over still rougher ground, watching intently lest any should attempt to escape. Over the top of the hill and down the slope they went, faster and faster, until, still well bunched, the brook was passed and they were going uphill toward the first pair of flags. Then one of the sheep made a bolt toward the lower part of the crag, but Laddie turned it back quick as a flash, thereby saving much time. Once more they made for the opening between the two flags that seemed to be planted so very close together. When quite near, they hesitated and had to be urged on. As soon as they started in the right direction Laddie lay down and watched them as they walked slowly along, leaving the flags on either side.

Looking toward his master for new directions, he quickly overtook his charges, who were slowly making their way for the hilltop, and, turning them in the direction of the next flag, now forced them into a gallop. Over the rocks they went, surefooted as goats, frequently lost to view among the bracken, but each time reappearing with the gray dog close at their heels.

Nearer and nearer they came, to within six feet of the flags, and seemed to be going well, when suddenly, without warning, they galloped off on the wrong side. The bracken was so high that the poor dog had not seen the second mark. “Coom t’me, lad! coom t’me!” shouted his master, and then the dog realized that a mistake had been made, and ran to a clear piece of ground, from which he could see his master and get his signals. The sheep, fortunately, had stopped soon after passing the flag, and the dog understood that they must be driven back outside the mark (for such is the rule), then turned sharply round and brought between the two flags.

How he understood it is difficult for us to realize, but that he did was proved by his actions; try as the sheep might to go the wrong way, Laddie, now coaxing, now forcing them, soon had all three in position for starting again for the narrow way that led between the two fluttering flags.

“T’hame, Laddie! t’hame!” called his master; and Laddie turned those sheep sharply round and brought them between the two red and white flags at full gallop.

It was well done, and the people gave the dog three subdued cheers—subdued because much noise would have distracted his attention. For this reason you seldom hear much shouting or clapping of hands until after the penning has been accomplished.

Sheep and dog came rapidly toward the pen, jumping the high bracken, dodging thick clumps of heather, and scrambling over loose rocks. Straight as a die they came until they were within a hundred yards or so of the pen, when Laddie was signalled to lie down, while the sheep, no longer driven, were glad of the opportunity to rest. J. K., leaving the knoll, came running down among the heather that clothed the steep hillside, to help at closer quarters in the penning. The trial was a near thing, for only one minute and twenty seconds of the allowed time remained, and the penning is a difficult matter, which requires care as well as time. The pen consists of three hurdles, the entrance being but wide enough to admit a full-sized sheep. Standing as it does in the open, without anything in the way of a path leading to it, it is the very last place that a sheep would think of entering of its own accord.

J. R. stood on one side of the pen and beckoned Laddie to bring the three scared-looking sheep forward. Slowly they came until near the goal; then, before man or dog could stop them, all three bolted past, and fully half a minute was lost in bringing them back.

At last, by coaxing ever so gently, they were taken to the pen, and two were passed through the narrow entrance and penned. The third, however, turned at the critical moment and bolted.

Time was nearly up; but a few seconds remained. Could the animal be recovered before those seconds had passed?

The spectators held their breath and watched intently; the time-keeper stood, watch in hand, ready to call the fatal word “Time,” while the man and the dog were working with nervous energy. It was a race against the second-hand of a watch, and the odds were in favor of the secondhand. Fortunately the two sheep in the pen had remained there, so the undivided attention was given to bringing in the third, which had run about fifty yards before Laddie could turn it. Back they came, the driven and the driver, until once more they were close to the pen. Then the dog dropped down, with his head on his paws, watching the sheep as it stood near the narrow entrance.

Nearer and nearer came the man, with arms outspread, while the dog crawled on his belly toward the staring, panting sheep. Once the sheep turned, as though to run, when, quick as a flash, Laddie stood up and took a step forward, ready to cut off the retreat; but the sheep, thinking better of it, turned toward the pen, and, after hesitating a moment, slowly entered, one second ahead of time.

It was a good piece of work; the dog had missed no points, had made some good retrieves, and had penned his sheep within the required time. So the crowd gave the plucky fellow three hearty cheers that bounded against the rocky sides of the mountain, and went echoing over the fells and fens until lost to hearing.

Of the many other dogs entered in the first class, but few were as fortunate as Laddie. Some were unlucky enough to have a bad trio of sheep—and much depends on how the sheep behave. Some are wild and will not run together; others travel too fast and cannot be checked; while others again are too slow and require constant urging. One of the dogs lost control of his sheep at the very commencement, each of the three running in a different direction, and the dog, though a good oneb(as he proved himself in the open stakes, which he won), was unable to collect them in the time allowed. The first class was won, not by Laddie, but by an old dog named Jack, who gave one of the finest exhibitions of the day, making some wonderful retrieves, keeping his sheep well in hand, while he completed the course and penning in seven minutes and thirty seconds.

The next class was run during the extreme heat of the day, and now it was that the tantalizing brook proved a temptation too strong for many of the dogs. One dog who was doing good work owed his failure to the strains of music that came across the hills from a band of itinerant musicians who, with an eye for gain, had taken their stand near the crowd of spectators. Their lively tunes distracted the dog, very much to his master’s disgust, and he became confused by the strange mixture of sounds, and lost many minutes in his endeavors to understand his master’s orders.

The time for this, the second class, was reduced to eight minutes, and of the thirteen dogs entered only one penned within the time without missing a point. That fortunate dog was Laddie, who had a minute to his credit when the sheep were safely in the pen.

One of the shepherds lost his temper completely because his dog, a young one, little over a year old, gave tongue when the sheep refused to do his bidding. It is against the rules and regulations for a dog to bark during the trials, and as the young dog broke these rules, his master’s voice came ringing through the air. He cried out angrily, “Shoot yo’ mouth, will ye! Hae ye nowt better to do than yowl? What’ll yon people think on ye, ye miserable yowling tyke! I’ll make it proper hot for ye, an’ I get ye hame, oor I’m gradely mistaken.” Whether or not he made it “proper hot” for the dog was not known, but the people said his anger was to some extent justified.

It will be noticed by any one who witnesses the sheep-dog trials that the actual penning within a certain limit of time does not always call forth the greatest amount of applause, for so much depends, of course, on how the sheep behave. The dog that does well with difficult sheep, making good recoveries and generally handling them well, receives far more of the public’s commendation, and certainly deserves more, than the dog who chances to have a set of sheep that are easily worked.

At the conclusion of the trials three prizes were given to the handsomest collies competing. When the name “collie” is used, it must be understood that these dogs are not the handsome, heavily coated dogs known in Cumberland as “fancy collies,” but more or less shaggy dogs with not very thick coats. They are lighter in build and rather longer than the fancy collie, and vary greatly in color – black, black and tan, blue, gray, and sable being the colors usually seen.

From the point of view of the amateur photographer, the sheep-dog trials are a great disappointment, as no spectator is allowed within about a hundred and fifty yards of the course, and it was only through the extreme kindness and courtesy Mr. A. B. Dunlop, the honorary secretary, and prime mover in the trials, that I was allowed the freedom of the grounds, with the privilege of using the camera.

Excerpted from Everybody’s Magazine – August 1902

Wow, what an excellent find. It’ll take me a while to process all the great info, but some first impressions come to mind. (1) The roughness of the terrain. (2) The lightness of the dogs. They looks to be sable or very light tri colors. I think only one of them has black on him. (3) That last dog is very familiar. I’ve seen him/her in another photo, I’ll have to look it up. That’s a real distinctive head, sort of like a Beardie/Collie cross.

Thanks Christopher, I actually stumbled upon this while doing research for that Border Collie article I have been telling you about and just had to put it right up.

I think all the action shots are the same dog, I’ll have to look up the captions on those photos, I should have added them from the start but I was lazy. If it is the dog in the story then he is described as “gray”, could that perhaps mean merle? He doesn’t look merle to me but in those black and white photos it may be hard to tell.

I found the similar looking dog to the last photo. Herdsman’s Tommy ISDS 16

http://www.bordercolliekennel.nl/Herdmans_Tommy_type_bc.jpg

It’s not really a look you see too much in the BC breed any more.

A. Radclyffe Dugmore’s photographs were used to illustrate some editions of Bob, Son of Battle. The photo on page 80 of the 1898 edition appears to be the same dog as the one in the photo above captioned “The gray dog at home.” Several of the other photos above are also in the book. I recall reading somewhere that he went on two trips to the region to take the photos.

These pictures are awesome, stories about sheep-dog trials from this age are not unusual but rarely are they so well illustrated. I can just imagine Mr. Dugmore navigating this rough terrain with one of those big cameras they used in those days, without any telephoto lenses, trying to get these good action shots without getting in the way. I know he must have really worked his tail off to get the shots he did.

I will have to do some research to see if I can find any more of his sheep-dog pictures.

What a lovely website. I can’t wait to have time to peruse the whole thing. Wonderful information.

Kyt

A pot of gold. Exceedingly important history of the Border collies forebears.Laddie is undoubtedly a beardie, beardie cross.Much more quality has been bred into the dogs since then, ie a low tail carriage, eye & style. Showing dogs became very popular in Victorian times and there is no doubt in my mind various crosses were introduced and much close breeding took place. I believe The Scotch collie to be a show dog with Russian Borzoi in it’s breeding, now known as a Rough collie.

A Gem of a web-site. What a find for enthusiast & historian alike.

Thanks for this fascinating article. Iris Combe, in her book, “Herding Dogs, their Origins and Development in Britain”, talks about the role of the Borzoi in the breeding of collies. She says that it was hoped by crossing Borzois which had been sent by the Russian Czar (as presents to the royal family) and collies in the royal kennels in Britain, to improve the stamina of the Borzoi. It was intended to take these collie/Borzoi crosses back to Russia to improve the stock there. But events at the time made it impossible to follow the progress of these dogs. Beautiful puppies were produced as a result of these crosses and many were given away and some exhibited. These “collies” became known as the Borzoi type. We still get heads of this type in modern show collies

Excellent article …so interesting to see how these men were dressed…people always dressed for the occasion but…not sure the straw boater is in keeping with dog trialing…..I prefer the flat cap 🙂

On the borzoi/collie cross….only recently I saw a picture of a smooth collie with the borzoi head which I really prefer on the borzoi, but, I’m certain the collie was a wonderful dog at home….they always are……..thanks for this Dianne 🙂